by Charles A. Kauffman

York College of Pennsylvania

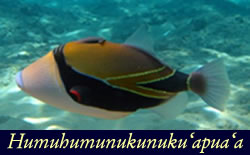

In Hawaii, the state fish is called Humuhumunukunuku‘apua‘a, a word that employs reduplication which involves duplicating sounds to emphasize key aspects of the word and its meaning (“pig-like, short-snouted fish” – a triggerfish). In the world of linguistics, the term reduplication seems in itself to be ‘redundantly reiterative,’ for, after all, isn’t duplication the act of doubling something? Why the prefix re- (to do again)? Why not use the term doubling or, simply, duplication? From the Latin re- ‘again’ + duplicare ‘fold’ or ‘double,’ what is implied is the act of doubling sounds or entire words. Despite the arguments against redundantly coupling the meaning of the prefix re- to the word duplication, in linguistics the term reduplication has been widely accepted as the norm for well over a century or more. This superfluous debate over re-/duplication notwithstanding, the practice of (re-)duplicating words, roots, stems and contrived forms is found in most languages throughout the world – more in some and less in others. Many colorful examples of reduplication reflect upon the richness and uniqueness of language, thought and culture as expressed by those who use this form to create plurals, amplify meaning, change verb tenses or invent words to describe tangible or intangible parts of the world around us. Whether for practicality, necessity, amplification or animation, reduplicated words are a fascinating, and fun, aspect of language.

There are buses in Hawaii called Wiki-Wiki, duplicating the word wiki ‘fast,’ emphasizing that the bus service is VERY FAST. In South Africa, when one says hier-hier in Afrikaans, it implies ‘right here!’ And, in Kenya, a melon in Swahili is a tiki. The size of the melon gains emphasis through reduplication and is called a tikitiki, ‘a large melon.’ When one adds the Swahili word maji ‘water’ we arrive at tikitiki maji (or tikiti maji), ‘water melon.’ Speakers of Malay say bunga for ‘flower’ and duplicate it to make the plural form bunga-bunga, ‘flowers.’ In China, a young girl might be described in Mandarin as xiăo ‘small’ and her little sister could be describerd as xiăo-xiăo, ‘tiny, very small.’ To say this in English, we might say itty-bitty or teenie-weenie which is a duplicative form in linguistics called rhyming reduplication, and in less language-centric circles it is sometimes referred to as echoing or ricochet words.

Reduplication in language is a morphological type that – through doubling a word, element, root, or stem – enhances, emphasizes, amplifies, enlarges, diminishes, adds number or changes verb tense –to bring about significant meaning changes or shades of meaning. There are two basic forms – full reduplication and partial reduplication – and some related forms that apply the technique of doubling through rhyming or vowel change. Reduplication in some cultures is a form of informal wordplay that is chosen over dry straight-forward discourse to convey intensity, humor, and playfulness, while applying cutesy, tongue-tickling or whimsical sounds and words. Doubling sounds, whether in words or parts of words, enables verbalization of thoughts to come alive in a colorful manner. It is a form of seasoning that salts and peppers language. Which sentence is more fun to say? My dog likes to go slowly on a walk. -- OR -- My dog likes to ‘dilly-dally’ on a walk. And, consider the jocular Yiddish forms of shm- as in fancy-shmancy, a unique form that evolved from Yiddish speaking immigrants in New York and other parts of the northeast United States. That new deli in Brooklyn is fancy-shmancy, but too bad it’s owned by a real Joe Shmo (shmo = jerk).

Reduplication is common in some languages and less common in others. Some world languages are believed to be reduplication-free, having no inherent reduplication constructs. Yet, languages from most families around the globe apply some form of reduplication, notably in early baby-talk (ma-ma), onomatopoeia (bow-wow) and endearing name doubling (Jon-Jon). Some use very few forms of reduplication. Take the Italian repeated word expression piano-piano ‘softly-softly’ which is used to tell someone to take it easy, to relax, to proceed calmly. While rich both phonetically and in lexicon, Italian, however, has few examples of true reduplication. A sampling of world languages from various families, groupings or isolated distinctions that apply reduplication include: Indonesian, Tagalog, Javanese, Malay, Fijian, Samoan, Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese, Russian, Persian, Turkish, Arabic, Hebrew, Yoruba, Twi, Swahili, Basque, Kannada, Tamil, Hindi, Bengali, Sioux, Dakota, Paiute, Salish, Bella Coola, Fox, Ojibwa and Warlpiri. Reflecting a need in grammar, expression of thought or sign of culture, the language family that has multiple examples of reduplication is the Austronesian (e.g., Malayo-Polynesian) Family. The following Austronesian languages employ either full reduplication or partial reduplication, or both: Balinese, Chamorro, Fijian, Hawaiian, Indonesian, Malagasy, Malay, Maori, Rapanui, Samoan and Tagalog.

Applying repetitive sounds to result in change in meaning is distinguished by any of the following types which are best illustrated in examples.

1. Full Reduplication – entire words duplicated

This type of reduplication applies doubling of the entire word. The word is simply repeated, often to yield plurals or to give various levels of intensity to a thought. Take the example of Malay in such words as rumah ‘house’ which in the plural form reduplicates to become rumah-rumah ‘houses.’ In Russian, a reduplicative adverbial form chut’ ‘a bit’ makes something ‘a tiny bit’ as in Ya govoryu po-russki chut’-chut’. ‘I speak Russian a tiny bit.’ The Swahili word choko ‘poke at’ takes on the meaning ‘discord, trouble’ when fully reduplicated to chokochoko. Speakers of various forms of Arabic (e.g., Juba) use full reduplication such as ketír ‘many’ → ketír-ketír ‘very many’ and neshíf ‘dry’ → neshíf-neshíf ‘completely dried out.’ Hawaiian language has many expressions built upon full reduplication: wali ‘smooth’ → waliwali ‘easy-going,’ ‘olu ‘cool, soft’ → ‘olu‘olu ‘good-natured,’ niho ‘tooth’ → nihoniho ‘serrated, saw,’ kiko ‘dot’ → kikokiko ‘freckled, spotted’ and kihi ‘tip, corner’ → kihikihi ‘zigzag.’

2. Partial Reduplication – parts of words (element, root, stem) duplicated

This type of reduplication uses a part of the words, typically a syllable that is repeated, and not the entire word. Take the Hebrew word chatul ‘cat’ which inserts -ta- to change the word’s structure and meaning to chatatul ‘kitten.’ The Māori language of New Zealand internally produces some nouns through partial reduplication of one element of the word. Take the examples: wahine ‘woman’ → waahine ‘women’ and tangata ‘person’ → taangata ‘people, persons.’ Moreover, Māori distinguishes subtleties using reduplication as in paki ‘to pat’ → partially reduplicated papaki ‘to clap one time’ → fully reduplicated pakipaki ‘to applaud.’ From Karok, an indigenous language of northwestern California, the word páchup ‘kiss’ is partially reduplicated in pachúpchup ‘kiss a lot.’ (Crystal)

3. Reduplication in Baby-Talk – simplifying words as baby acquires language

As infants begin to develop speech, reduplication is an important feature of their phonologies. (Crystal) Words that the baby can understand but not quite articulate completely are easier to shorten into doubled syllables such as water which becomes wawa, bottle becomes buh-buh, blanket becomes bay-bay and so forth. As infants discover the ability to speak, they typically develop words such as mama, dada, papa, boo-boo, poo-poo, bye-bye and a whole array of words for grandparents (e.g., pop-pop, gan-gan), many of which are reinforced by parents or caregivers. Children universally develop the art of reduplication (but not to the same extent) and use it until an age that they are able to pronounce words fully. The disappearance of reduplication happens at different ages and depends upon reinforcement by adults in the child’s life.

4. Rhyming Reduplication – different words with near duplicated sounds resulting in rhyming

In English there is a large collection of rhyming reduplication expressions: itsy-bitsy, chick-flick, teenie-weenie, fender-bender, lovey-dovey, hanky-panky, fuddy-duddy, hoity-toity, hodge-podge. Not all languages in the world use rhyming, but Russian is one that gives us many examples: plaksa-vaksa = crybaby, kashka-malashka = porridge, krestiki-noliki (crosses, zeroes) = tic-tac-toe or noughts and crosses, pravda-krivda (truth, crookedness) = distorted truth, and ruki-kryuki = clumsy hands. (Voiner)

5. Ablaut Reduplication – changing vowels of words that nearly rhyme

Altering vowels to produce near-rhyming outcomes results in such reduplicative forms as: chit-chat, zig-zag, tick-tock, criss-cross, pitter-patter, mish-mash, bric-a-brac and many more. This form is less prolific in world languages. Japanese uses kasa-koso ‘rustle’ and gata-goto ‘rattle’ and Chinese has pīlipālā ‘splashing.’

6. Reduplication in Onomatopoeia – imitating animals and sounds in nature

Onomatopoeia has been a language universal since man developed the inherent ability for language. Imitation of sounds such as a dog’s bow-bow to a Japanese speaker is wanwan, to a Russian gavgav, to a Spanish speaker gufguf, a Korean mungmung. A bee’s buzz is bzzz-bzzz in French and Spanish, it’s zoum-zoum in Greek, zh-zh-zh in Russian and buzz-buzz in Swedish. A rooster crowing in Italian is chichirichi, in Spanish is quiquiriquí and in German is kikeriki. The word dokidoki is Japanese onomatopoeia for ‘heartbeat’ and barabara refers to ‘rain pouring down.’ In Japanese byun means ‘spin’ but byunbyun means ‘whizzing by.’ Onomatopoeia is full of reduplication.

7. Name Doubling (Reduplication) – primarily used for close relationships, imparting an endearing quality that implies a quality of likability. This form is common in English and Chinese.

Take some English nicknames for example: Jon-Jon, Lou-Lou, BeBe, JoJo, Jay-Jay, Mo-Mo. These types of first names can come from a variety of sources and reasons. They add an affable quality to the way an individual addresses a friend or family member. The name of the famous French-born Chinese-American cellist Yo-Yo-Ma is not an intended form of reduplication. Yo, ‘friendly’ in Chinese, was “duplicated” to Yo-Yo, according to the master musician himself in an interview, since his sister’s name is Ma-Yo Chang. In the Philippines it is quite common to reduplicate first names as a friendly gesture of endearment. In France children sometimes call their uncle tonton.

There are some languages (e.g., Chinese) that reduplicate elements for their surname. The name of the Hawaiian King Kamehameha (ka = the meha = quiet) means ‘the very quiet, (solitary) one.’ Place names around the world also employ reduplication in such examples as Baden-Baden (Germany), Puka Puka (Cook Islands), and Tawi Tawi (Philippines).

8. Shm- Reduplication – deprecative reduplication indicating irony, sarcasm, skepticism rhyming base words with the prefix shm- ___.

This form of reduplication originated with Yiddish speaking Jews who settled mainly in the New York area and spread to non-Yiddish speakers in the northeast U.S. In Yiddish-inspired English it is used to convey irony, sarcasm, skepticism, wit, poking fun and more by applying shm- (also written schm-) to the duplicated base word after dropping the initial consonant(s). Bagel-shmagel, I want a full meal! Money-shmoney, you should think it grows on trees? Help-shmelp, they just stood around and watched us work!

Applying repetitive sounds result in grammatical or lexical distinctions which make profound or subtle changes in meaning. Here again, the various uses of reduplication are best illustrated in examples.

1. Forming plurals – Creating plurals via reduplication is seen in languages either in full or partial form. In Indonesian, the word kapal ‘ship’ simply becomes two or more in kapalkapal ‘ships,’ a form that doubles the entire word. In Dinka, a Nilo-Saharan language spoken in southern Sudan, some plurals are formed through internal reduplication of vowels: pal ‘knife’ becomes paal ‘knives’ – gālám ‘pen’ becomes gālâam ‘pens.’ Some plurals in the Austronesian language Samoan use the same form of internal reduplication, for example, le tamaloa ‘the man’ changes to tamaloloa ‘the men.’

2. Verb tenses – Reduplication is used to change tenses with a simple doubling of the first element to indicate future or perfective tense. In ancient Greek, the perfective was constructed by doubling the first element of the verb, as in leipo ‘I leave’ → léloipa ‘I have left.’ In some languages, notably, among the Austronesian languages, the future tense is formed through partial reduplication. Tagalog, spoken in the Philippines, provides excellent examples of this form.

Tagalog repeats a consonant-vowel sequence to form the future tense:

| tawag ‘call’ | ta + tawag → | tatawag ‘will call’ |

| sulat ‘write’ | su + sulat → | susulat ‘will write’ |

| hanap ‘seek’ | ha + hanap → | hahanap ‘will seek’ |

| lakad ‘walk’ | la + lakad → | lalakad ‘will walk’ |

(Pereltsvaig)

3. Intensity, Amplification, Enhancement – Doubling of entire words or stems enhances or significantly changes the quality of the idea intended by the word. In Finnish, the word kauas means ‘far away.’ Reduplication amplifies kauaskauas to mean ‘far far away.’ This is similar to the Russian davnym-davno (or, davno-davno) which means ‘a long long time ago.’ Relating to this, the Russians playfully use the rhyming reduplicative expression davno-gavno which means ‘It’s been crap for a long time.’ In Chinese, shēnyuăn ‘far-reaching’ reduplicates to shēnshēnyuănyuăn by juxtaposing like elements from the original word resulting in amplified distance, ‘far-far reaching.’ The Hawaiian word nula ‘wave’ significantly amplifies the size of the wave when reduplicated – nulanula → ‘huge wave, tidal wave.’ To state that something is absolutely beautiful in Chinese, both elements of piàoliang ‘beautiful’ are reduplicated – piàopiàoliangliang. An expression in Nepalese, rangi-changi, is used to describe something that is extremely vivid and colorful, or something of great energy, complex to the point of being chaotic. One of those hard to translate words, the term rangi-changi can be used in reference to an intense work environment or an exciting night club. In Swahili piga means ‘to strike’ whereas pigapiga implies repetition, ‘to strike repeatedly.’ There is an example in a dialect of Indonesian in which the word igi ‘many’ is reduplicated four times, igi-igi-igi-igi meaning ‘more numerous than anything.’ (Lord)

4. Specificity – Some languages and the cultures that speak those languages apply a form of specificity to make certain there is no doubt about the meaning intended. In Norwegian, Danish and Swedish, the word mor means mother, whereas mormor means ‘mother’s mother’ (maternal grandmother). Far means ‘father’ and farfar means ‘father’s father’ (paternal grandfather). Further, morfar means ‘mother’s father’ (maternal grandfather) and farmor means ‘father’s mother’ (paternal grandmother). So, there is no doubt which grandparent a child is talking about. In English, if two teenage girls are chatting about a boy, you might hear one ask Do you like him? Or do you like-like him? Here, like-like is taken to mean Do you REALLY like him? Compare this to the Finnish word ruoka ‘food’ with ruokaruoka ‘proper food’ (in contrast to snack food). The Finns also make a distinction between the sense of ‘home’ koti versus ‘home where you grew up’ kotikoti, i.e, ‘your parents’ home.’ And, if you drink coffee at Starbucks, you might try “Katikati,” the Swahili-inspired ‘medium’ blend from Kenya described as kati ‘medium’ but set fully in the mid-range of your palate by katikati ‘middle-middle,’ specifying it is exactly in the middle between the flavors of light and dark beans.

5. Diversity and Collectivity – To distinguish between one thing and a group of that thing reduplication forms are used. Examples of this usage from Austronesian languages include: Indonesian anak ‘child’ becomes anak anak to signify ‘all sorts of children.’ (Pereltsvaig). Malay daun ‘leaf’ becomes a collection using daun-daunan ‘foliage, leaves’ and sayur ‘vegetable’ when reduplicated in rhyming form sayur-mayur renders the meaning ‘various vegetables.’ (Comrie) An example in Farsi, a rhyming form, xert-o-pert refers to ‘odds and ends.’

6. Similarity – In reduplicating the lexeme, the doubled form often relates closely to the original as in the Indonesian word kuda ‘horse’ which becomes kuda kuda to signify ‘saw horse.’ (Comrie). The Indonesian word langit ‘sky, heaven’ is rendered into a related meaning when reduplicated – langit-langit meaning ‘ceiling.’

7. Playfulness – The English expression razzle-dazzle brings life to what is being described. The razzle-dazzle of that basketball team made the entire game exciting to watch. Conversely, in Farsi, reduplication is sometimes used to mock words of non-Persian origin. At German beer festivals one might hear the phrase Zicke zacke zicke zacke hoi hoi hoi. While there have been attempts to make sense of the reduplicated phrase, it merely represents a bunch of nonsensical sounds that together are fun to chant out after a few mugs of brew. But, in German colloquial language, zack-zack is used to say ‘Get going!’ (which corresponds to English chop-chop). The German Misch-Masch corresponds also to English hodge-podge. Usage of shm- reduplication is frequently used for humor or poking fun. Dead-shmead, Yiddish is still a spoken language!

8. Aimlessness and Vagueness – Words or stems doubled may be used to signify doing something willy-nilly, haphazardly, without direction or distinct purpose, or to denote a lack of distinction. Dĕng in Chinese means ‘to wait’ but gives an open-endedness when reduplicated – dĕngdĕng ‘to wait for a while.’ In Malay, duduk means ‘sit’ but when reduplicated, duduk-duduk mean ‘sit around doing nothing.’ And, mérah means ‘red’ but to indicate reddish, the reduplicated form kemérah-mérahan is constructed. (Comrie) In Turkish yeşil ‘green’ has a rhyming duplicative yeşil-meşil that means ‘greenish.’ Finally, in Tagalog, linisin means ‘to clean’ and linis-linisin means ‘to clean a little.’ (Comrie) In Japanese, the word fura ‘drift, dizziness’ when reduplicated to furafura means ‘to roam or to hang out with no intended aim or purpose.’

9. Reciprocity – Reduplication takes on a reflexive characteristic in some languages such as Malay in the example hormati ‘respect’ which becomes reflexive in ormat-menghormati ‘to respect each other.’ (Comrie)

10. Statements on Life – In Fijian the word bula, literally, ‘life’ is similar to Hawaiian Ahoha (‘peace, love, calm’) in that it encompasses an aspect of life that is not translatable to an exact word, or at least has multiple senses of the word. Bula-bula, used for ‘Hello,’ ‘good-bye,’ ‘welcome,’ or a blessing when one sneezes, refers to ‘Here’s to life’ and it comes from the hearts of Fijians. The Swahili expression Hakuna wasi wasi ‘no worries’ is based on the word wasi ‘concern, doubt.’ The Japanese art of finding beauty from imperfection is called wabi-sabi, a rhyming reduplicated term that embodies looking past the blemishes on a face and cracks in walls to find inherent beauty. Wabi stems from the Japanese wa- meaning ‘harmony, peace, tranquility,’ whereas sabi means ‘the bloom of time.’

Linguist Ken Sakoda, provides an excellent example of reduplication in Hawaiian Creole – a mix of Hawaiian, English, Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Portuguese – that his mother used to say:

You likee banana you wiki-wiki kau-kau mai-tai.

You likee = English, wiki-wiki = Hawaiian ‘quickly’, kau-kau = Chinese ‘eat’, mai-tai = Tahitian ‘good’

~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~:~

To you readers who find reduplication a fascinating aspect of language, thought and culture:

Bula-Bula !

Comrie, Bernard. The World’s Major Languages. Oxford University Press. 1990

Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge University Press. 1997

Lord, Robert. Comparative Linguistics. The English Universities Press. 1974

Pereltsvaig, Asya. Languages of the World. Cambridge University Press. 2012

Voiner, Vitaly. “Rhyming Reduplication in Russian Paired Words.” Russian Linguistics. Apr 2012

Charles A. Kauffman is a professor of Indo-European and World Languages courses within the English & Humanities Department at York College of Pennsylvania, United States. He is a retired U.S. Government linguist who worked with multiple languages for over 30 years. He also teaches Russian, German and Italian and is a frequent speaker on topics relating to language and culture.

Contact information: ckauffm8@ycp.edu (York College of Pennsylvania)

You can also download a PDF of this article.

Writing systems | Language and languages | Language learning | Pronunciation | Learning vocabulary | Language acquisition | Motivation and reasons to learn languages | Arabic | Basque | Celtic languages | Chinese | English | Esperanto | French | German | Greek | Hebrew | Indonesian | Italian | Japanese | Korean | Latin | Portuguese | Russian | Sign Languages | Spanish | Swedish | Other languages | Minority and endangered languages | Constructed languages (conlangs) | Reviews of language courses and books | Language learning apps | Teaching languages | Languages and careers | Being and becoming bilingual | Language and culture | Language development and disorders | Translation and interpreting | Multilingual websites, databases and coding | History | Travel | Food | Other topics | Spoof articles | How to submit an article

[top]

You can support this site by Buying Me A Coffee, and if you like what you see on this page, you can use the buttons below to share it with people you know.

If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon, or by contributing in other ways. Omniglot is how I make my living.

Note: all links on this site to Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk

and Amazon.fr

are affiliate links. This means I earn a commission if you click on any of them and buy something. So by clicking on these links you can help to support this site.

[top]